Season 6, Episode 6: “Triangle”

Original Airdate: November 22, 1998

For a science fiction television program, The X-Files is not particularly interested in time travel. We’ve had fortune-tellers, missing time, and an old man who encouraged us to Fight the Future, but not so much with the landing in the past/waking up in the future. “Triangle”—which drops Mulder onto a Nazi-laden luxury liner in 1939—could have been the category winner, but, unfortunately, it’s more party trick than TARDIS up in here.

“Triangle” is one of the show’s Homages To, one of those Conceptual Concepts, one of those, wouldn’t-it-be-cool-ifs. It’s the spiritual twin of last season’s “Post-Modern Prometheus,” an episode that similarly ditched the show’s procedural backbone in favor of some genre trickery. This time it’s in the name of Rope, the Hitchcock film with the long takes and minimal editing. “Triangle” is done up similarly, the camera swinging around to create an impression of action-continuous. As stunts go, it’s not a bad one—it’s fun, actually, to watch the camera get clever, and The X-Files’ naturally dark corners make the edits fairly seamless. So why, then, does the episode feel so flat?

It’s the story, I’m afraid, and the time travel that isn’t. The episode opens with a long shot of Mulder, lying face-down in the water. He’s gone rogue again, taken some personal time to chase a ghost ship in the Bermuda Triangle—the Queen Anne, a British luxury liner that we’re told vanished-without-a-trace in 1939. Mulder comes to when he’s dragged aboard the ship by the vintage crew, the real crew, the 1939 crew. He thinks at first that the ship has time-traveled to 1998 (cheekily offering a Lewinsky joke to prove to the sailors that they need not be afraid of World War II any longer), then realizes that it’s the reverse, and he’s time-traveled to 1939. And also that the ship is carrying a secret weapon that must be protected from the Nazis—a scientist, a man who knows a little something about bombs comma atomic.

Except one thing, and I’m sorry, but Mulder hasn’t really time-traveled. Or at least, “Triangle” doesn’t offer much proof that he has. Mulder’s trip to 1939 functions like a dream, something he made up while passed out in the ocean. Everyone’s a little cartoonish, and everything’s a little fake, and although Scully and the Lone Gunmen later spot—and board—the mysteriously-visible Queen Anne in 1998, they find her empty. Mulder meanwhile sees a ship full of familiar faces, except none of them are who they are. They’re instead all playing roles. The Cigarette-Smoking Man appears as the leader of a crew of Nazis who have boarded the ship; Spender appears as his right-hand man. Skinner is a Nazi, too, except a sympathetic one who helps out at the end. And then there’s Scully, in a red dress and bobbed hair, working undercover for the OSS.

The Jungian casting—plus the episode’s incessant Wizard of Oz references—seals the dream logic for me. And it’s too bad, because this alone then torpedoes any investment that I have in the episode’s stakes, in Mulder hollering at people that they need to turn the ship around so that it never gets out of the Bermuda Triangle, so that in real life the Nazis never have control of a scientist who could make them an atomic bomb. You could argue—I guess you could argue—that maybe the Cigarette-Smoking Nazi is an actual real-life distant relative of the current Cigarette-Smoking Man, but that seems like a stretch. You could also argue that it’s sort of parallel universe? Which would be backed up by the episode’s trickiest-trick, the shot of Scully crossing the path of her 1939 look-alike and then the both of them stopping, like they’d crossed graves. But if it’s a parallel universe then what’s Mulder yelling about his own existence for, and shouldn’t he just be focusing on getting back to his own world before the Nazis win the parallel universe war?

It’s a muddy plot, to say the least, and it pains me to focus on it because other than that, yes that’s right other than the episode’s entire plot, “Triangle” is a lot of legitimate actual good-time fun. The double-dream-casting makes for plenty of fan-friendly moments, like the part where Mulder beats up a guy who attacks him and he’s not even sure who he is and then, surprise, it’s Nazi Spender. And the part where Nazi Skinner says, “God bless America. Now get your asses out of here.” And the part where OSS Scully threatens to punch Mulder because she thinks he’s a Nazi. And the part where everyone has a really, really terrible accent.

On the other side of the episode, the reality-based side, there’s Scully. You know, the one who isn’t lying face-down in the ocean? The one who isn’t delirious, the one who has yet to inhale salt water? The one who is running up and down the FBI, looking for an ally to help her pull her partner out of danger, again, because he’s done something stupid, again. These scenes—up the elevator, down the elevator; begging a favor, regretting a favor—are unexpected treats on re-watch. They might not have the flash and costume of the Queen Anne scenes, but they’ve got a clear goal, and that makes all the difference. Justifies the camerawork and allows us to enjoy rather than second-guess.

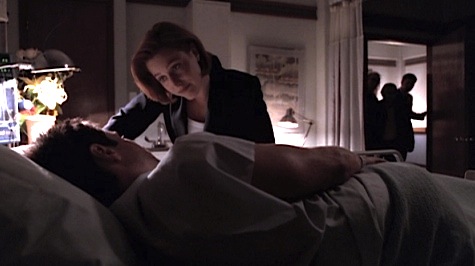

Of course we can’t get out of Mulder’s dream without one final piece of wish fulfillment, and if your heart is still bruised by The Bee Incident you may want to look away. To OSS Scully Mulder says, “in case we never meet again” then he kisses her, full-on, until she pulls back and punches (not slaps! punches!) him. He wakes up in a hospital and tells his partner “I love you,” and his partner says, “Oh, brother,” and there it is, will-they-or-won’t-they reduced to a running joke. A good trick, sure. But it’s not going to hold up for long.

Meghan Deans wants you to do her a favor: it’s not negotiable, either you do it or she kills you. She Tumbls and is @meghandrrns.